中世纪的圣母玛利亚崇拜(纽约大都会艺术博物馆)

来源:金玉米 编辑:admin

时间:2023-09-15

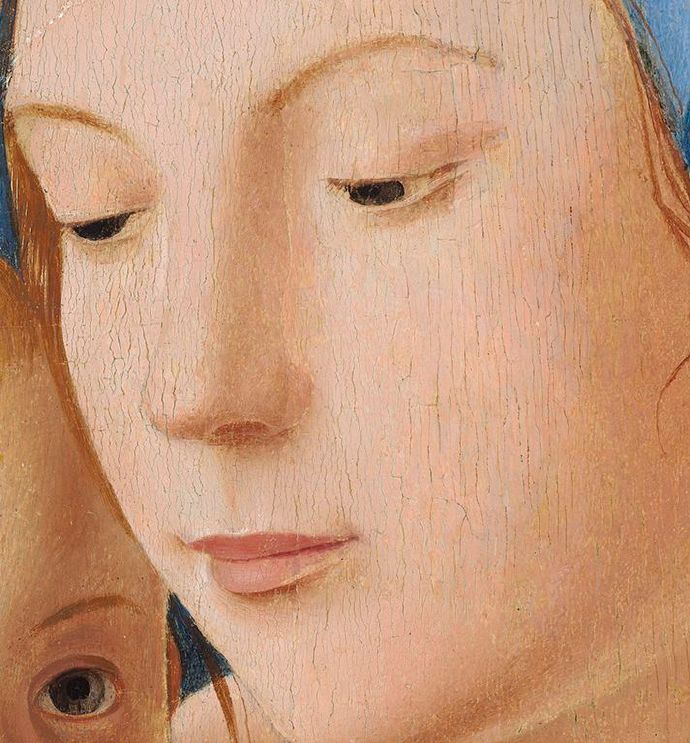

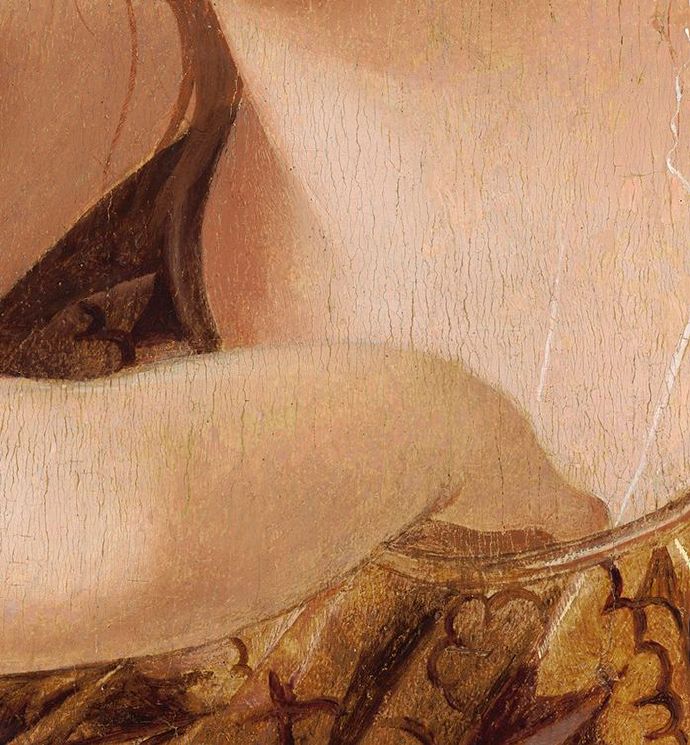

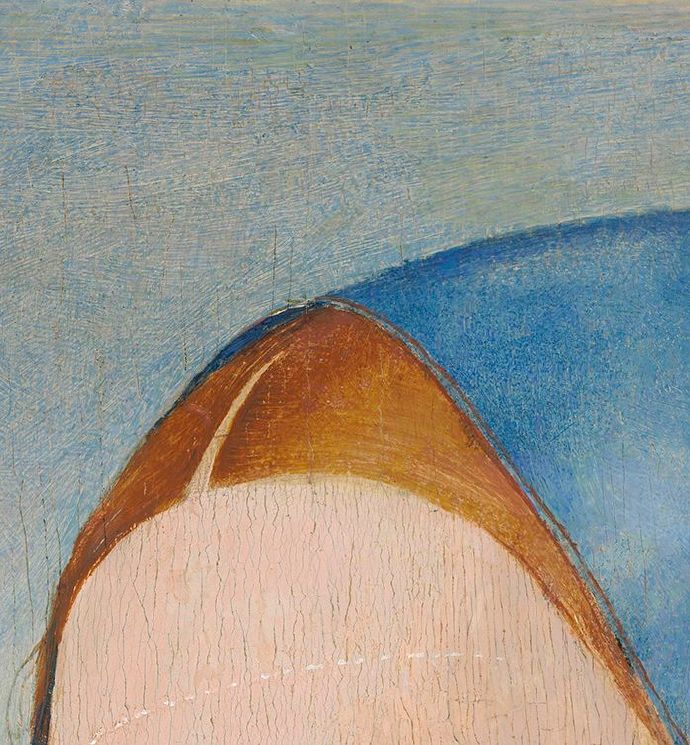

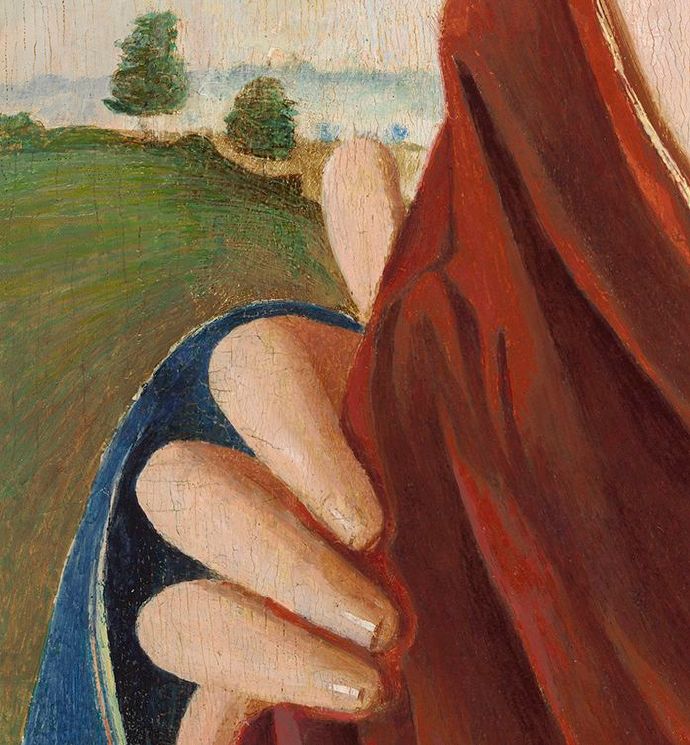

安托内洛·德·梅西纳 圣母子 Madonna with Child 华盛顿国家美术馆

海尔布伦艺术史时间表

中世纪的圣母玛利亚崇拜

大都会艺术博物馆 中世纪艺术系和回廊

2001年10月

圣母玛利亚和教会

在一些宗教中,母亲形象是崇拜的中心对象(例如圣母子的画面让人想起埃及伊希斯护理她的儿子荷鲁斯的图像)。历史上耶稣基督的母亲圣母玛利亚出自福音书的文本。她的传奇装饰似乎已经在五世纪的叙利亚形成。基督之母的生活是特殊的:她生来就没有了原罪(21.168),通过圣母无染原罪,她去世后被带到了天堂(17.190.132); 正如圣托马斯怀疑基督的复活,所以他怀疑玛丽的假设。神学家为基督的激情和圣母的同情之间建立了平行关系:当他在十字架上身体受伤时,她在精神上被钉在十字架上。431年以弗所议会批准圣母玛利亚为上帝的母亲; 不久之后,包含教会教义的圣母和儿童基督的形象开始传播。

巴纳巴·达·摩德纳 圣母子 Virgin and Child 巴黎卢浮宫博物馆

拜占庭代表中的圣母玛利亚

圣母玛利亚在希腊语术语中被称为“上帝的承载者”(Theotokos,上帝的母亲),是拜占庭精神的核心,是其中最重要的一个宗教人物。在作为受苦的人类与基督和人类的保护者之间的中介君士坦丁堡,她受到了广泛的尊敬。圣母是重要的礼仪赞美诗的主题,如在天使报喜节(3月25日)和四旬期间演唱的圣母颂赞美诗。基督的母亲的叙事艺术表现集中在她的观念和童年或她的安息(圣母的安息或永恒的睡眠)。大多数圣母像都强调她扮演基督之母的角色,展示她的立场并抱着她的儿子。圣母拥有基督的方式非常特别。某些姿势发展成“类型”,成为庇护所或诗意绰号的名称。因此,圣母的符号意味着代表她的形象,同时也是一个著名的图像原件的复制品。

吉皮特里诺 圣母子 The Virgin and Child 米兰波尔迪·佩佐利美术馆

“圣母指明道路”(Virgin Hodegetria)是圣母的一个受欢迎的代表,她在左臂上抱着基督并用右手向他示意,表明他是通往救赎的道路。Hodegetria这个词来自君士坦丁堡的霍德贡修道院(Hodegon Monastery),其中以特殊姿态显示圣母的图像至少从12世纪开始,用于保护城市。后来的类型是“温柔圣母”(Virgin Eleousa)的类型,形象想象来自Virgin Hodegetria。这种类型代表了圣母的富有同情心的一面。她被弯曲地抚摸着她的孩子的脸颊,她的手臂搂着她的脖子,让这种感情回报。西方采用了拜占庭圣母的形象。例如,早期的荷兰画作如处女和儿童(17.190.16)由圣厄休拉传奇和圣母子大师(30.95.280由Dieric Bouts揭示了对拜占庭圣母形象的兴趣。

罗吉尔·凡·德·韦登 圣母子 The Virgin and Child 美国费城艺术博物馆

西方代表中的圣母玛利亚

大多数西方类型的圣母像,如来自法国中部的十二世纪“智慧王座”,其中基督孩子 正面呈现为神圣智慧的总和,似乎起源于拜占庭(16.32.194)。到七世纪,拜占庭模型在西欧广泛分布。十二世纪和十三世纪西欧的圣母崇拜增长非常迅速,其中一部分灵感来自诸如圣伯纳德克莱尔沃(1090-1153)等神学家的着作,后者认定她是歌曲之歌的新娘在旧约中。圣母被崇拜为基督的新娘,教会的化身,天后的女王,以及拯救人类的中间人。这一运动在其中发现了最大的表现法国大教堂通常致力于“圣母”,许多城市,如锡耶纳,都将自己置于她的保护之下。

圣母玛利亚在中世纪晚期

罗马时期的僧侣的图像,强调玛丽的王室方面,让位于 哥特时代 更温柔的陈述(1999.208; 1979.402)强调母子关系。来自科隆的十四世纪早期的“打开圣母”(17.190.185)阐述了她在基督徒救赎中的作用。当关闭时,铰链雕塑代表圣母护理儿童基督,他持有圣灵的鸽子。她的衣服像三叶草的翅膀一样打开,在她的身体里展示父神的形象。他握着十字架,由两棵树干组成,现在缺少基督的身影。侧翼的翅膀上画着基督的初期或化身的场景,也就是说,人类肉体中的儿子上帝的化身。

【文献】

中世纪艺术系和回廊。“中世纪圣母玛利亚的崇拜。”在海尔布伦的艺术史时间表中。纽约:大都会艺术博物馆,2000-。http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/virg/hd_virg.htm(2001年10月)

贝尔汀,汉斯。相似与存在:艺术时代之前的形象史。芝加哥:芝加哥大学出版社,1994年。

Forsyth,Ilene H. 智慧王座:罗马式法国麦当娜的木雕。普林斯顿:普林斯顿大学出版社,1972年。

保罗·迪·乔凡尼·菲 圣母子 Madonna con il Bambino 意大利米兰布雷拉美术馆

原文

The Cult of the Virgin Mary in the Middle Ages

Department of Medieval Art and The Cloisters

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 2001

The Virgin Mary and the Church

A mother figure is a central object of worship in several religions (for example, images of the Virgin and Child call to mind Egyptian representations of Isis nursing her son Horus). The history of the Virgin Mary, mother of Jesus Christ, depends on the texts of the Gospels. Embellishments to her legend seem to have taken form in the fifth century in Syria. The life of the mother of Christ was exceptional: she was born free of original sin (21.168), through the Immaculate Conception; she was taken to heaven after her death (17.190.132); and, just as Saint Thomas doubted Christ’s Resurrection, so he doubted Mary’s Assumption. Theologians established a parallel between Christ’s Passion and the Virgin’s compassion: while he suffered physically on the cross, she was crucified in spirit. The Council of Ephesus in 431 sanctioned the cult of the Virgin as Mother of God; the dissemination of images of the Virgin and Child, which came to embody church doctrine, soon followed.

安托内洛·德·梅西纳 圣母子 Madonna with Child

The Virgin Mary in Byzantine Representations

The Virgin Mary, known as the Theotokos in Greek terminology, was central to Byzantine spirituality as one of its most important religious figures. As the mediator between suffering mankind and Christ and the protectress of Constantinople, she was widely venerated. The Virgin is the subject of important liturgical hymns, such as the Akathistos Hymn, sung at the Feast of the Annunciation (March 25) and during Lent. Narrative artistic representations of Christ’s mother focus on her conception and childhood or her Koimesis (her Dormition, or eternal sleep). Most images of the Virgin stress her role as Christ’s Mother, showing her standing and holding her son. The manner in which the Virgin holds Christ is very particular. Certain poses developed into “types” that became names of sanctuaries or poetic epithets. Hence, an icon of the Virgin was meant to represent her image and, at the same time, the replica of a famous icon original. For example, the Virgin Hodegetria is a popular representation of the Virgin in which she holds Christ on her left arm and gestures toward him with her right hand, showing that he is the way to salvation.

安托内洛·德·梅西纳 圣母子 Madonna with Child

The name Hodegetria comes from the Hodegon Monastery in Constantinople, in which the icon showing the Virgin in this particular stance resided from at least the twelfth century onward, acting to protect the city. A later type is that of the Virgin Eleousa, imagined to have derived from the Virgin Hodegetria. This type represents the compassionate side of the Virgin. She is shown bending to touch her cheek to the cheek of her child, who reciprocates this affection by placing his arm around her neck. Byzantine images of the Virgin were adopted in the West. For example, Early Netherlandish paintings such as the Virgin and Child (17.190.16) by the Master of the Saint Ursula Legend and the Virgin and Child (30.95.280) by Dieric Bouts reveal an interest in Byzantine representations of the Theotokos.

安托内洛·德·梅西纳 圣母子 Madonna with Child

The Virgin Mary in Western Representations

Most Western types of the Virgin’s image, such as the twelfth-century “Throne of Wisdom” from central France, in which the Christ Child is presented frontally as the sum of divine wisdom, seem to have originated in Byzantium (16.32.194). Byzantine models became widely distributed in western Europe by the seventh century. The twelfth and thirteenth centuries saw an extraordinary growth of the cult of the Virgin in western Europe, in part inspired by the writings of theologians such as Saint Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153), who identified her as the bride of the Song of Songs in the Old Testament. The Virgin was worshipped as the Bride of Christ, Personification of the Church, Queen of Heaven, and Intercessor for the salvation of humankind. This movement found its grandest ex-pression in the French cathedrals, which are often dedicated to “Our Lady,” and many cities, such as Siena, placed themselves under her protection.

安托内洛·德·梅西纳 圣母子 Madonna with Child

The Virgin Mary in the Later Middle Ages

The hieratic images of the Romanesque period, which emphasize Mary’s regal aspect, gave way in the Gothic age to more tender representations (1999.208; 1979.402) emphasizing the relationship between mother and child. The early fourteenth-century Vierge Ouvrante (17.190.185) from Cologne articulates her role in Christian salvation. When closed, the hinged sculpture represents the Virgin nursing the Christ Child, who holds the dove of the Holy Spirit. Her garment opens up, like the wings of a triptych, to reveal in her body the figure of God the Father. He holds the cross, made of two tree trunks, from which the now-missing figure of Christ hung. The flanking wings are painted with scenes from Christ’s infancy or Incarnation, that is to say, the embodiment of God the Son in human flesh.

Citation

Department of Medieval Art and The Cloisters. “The Cult of the Virgin Mary in the Middle Ages.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/virg/hd_virg.htm (October 2001)

Belting, Hans. Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image Before the Era of Art. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994.

Forsyth, Ilene H. The Throne of Wisdom: Wood Sculptures of the Madonna in Romanesque France. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972.

作品细节

安托内洛·德·梅西纳 圣母子 Madonna with Child

安托内洛·德·梅西纳 圣母子 Madonna with Child

安托内洛·德·梅西纳 圣母子 Madonna with Child

安托内洛·德·梅西纳 圣母子 Madonna with Child

安托内洛·德·梅西纳 圣母子 Madonna with Child

安托内洛·德·梅西纳 圣母子 Madonna with Child

安托内洛·德·梅西纳 圣母子 Madonna with Child

安托内洛·德·梅西纳 圣母子 Madonna with Child

安托内洛·德·梅西纳 圣母子 Madonna with Child

安托内洛·德·梅西纳 圣母子 Madonna with Child

安托内洛·德·梅西纳 圣母子 Madonna with Child

安托内洛·德·梅西纳 圣母子 Madonna with Child

安托内洛·德·梅西纳 圣母子 Madonna with Child

画家简介

安托内洛·德·梅西纳(Antonello da Messina,约1429-1479),文艺复兴时期意大利画家。文艺复兴时期意大利艺术理论家乔尔乔·瓦萨里(Giorgio Vasari,1511-1574)在他的艺术家传记中称,安托内洛第一个将油画引入到意大利。安托内洛的风格以其意大利简约与弗拉芒绘画对细节的关注而著称。他对意大利绘画产生了巨大影响,不仅通过佛兰德艺术的引入,而且通过佛兰芒绘画的传播。

安托内洛出生于意大利西西里岛城市墨西拿,曾经是那不勒斯画家尼科罗·安东尼奥·科兰托尼奥(Niccolò Antonio Colantonio)的学生。他的作品表现出早期荷兰弗拉芒绘画的强烈影响,表明他深入研究过罗吉尔·范德韦登(Rogier van der Weyden, 1399-1464)和扬·凡艾克(Jan van Eyck,1385-1441)的作品。有研究表明,安托内洛在1456年访问了米兰,在那里他可能遇到了范艾克最有成就的追随者佩特鲁斯·克里斯蒂(petrus christus,约1410-1476)。由于安托内洛是第一批掌握凡艾克油画的意大利人之一,而克里斯蒂是第一位学习意大利线性视角的荷兰画家,这次会面解释了两位艺术家风格演变和肖像画的相似。

历史学家认为,安托内洛在十六世纪六十年代后期绘制了他的第一幅肖像画。他们遵循荷兰模式,主题显示胸围,深色背景,全脸或四分之三视图,而大多数以前的意大利画家采用了奖章式的个人肖像轮廓姿势。约翰·波普-汉尼斯(John Pope-Hennessy)形容他是“第一位个人肖像本身就是艺术形式的意大利画家”。

安托内洛于1475年到1476年秋天呆在威尼斯。他的作品显示出对人体形象的更多关注,包括解剖学和表现力,表明皮耶罗·德拉·弗朗西斯卡(Piero della Francesc,约 1412-1492)和乔瓦尼·贝利尼(Giovanni Bellini,约1430-1516)的影响。他的半身肖像画采用3/4的视野画法,综合了佛兰德斯绘画的细腻和意大利绘画的华丽,在当时蔚为风气。他那不用线与影而用色彩塑造形体的的绘画手法深深影响了威尼斯绘画发展。